Politics and portfolios

‘May you live in interesting times’

Old Chinese curse.

What a mess

It is rare that politics is discussed in our articles about investing, but it is evident when turning on the news that it feels like there is much going on in global politics at the moment that is unsettling, complex and confusing at one end, such as Brexit, to the downright worrying and unpleasant at the other, such as Russian meddling in the democratic process and the use of nerve agents on the streets of Salisbury. There is much in between that is hard to compute in terms of its impact. Trump’s populism feels unpleasant to many, but is his call to NATO members, such as Germany, to meet their commitments in full to share more of the financial burden of protecting Europe unfair, given Russian aggression? Is his trade war with China wholly a bad thing? A recent leader in The Economist[1] supports – at least in part – his tirade against its mercantilism and unfair trade practices. Let’s not forget climate change…

Issues closer to home such as Brexit and the potential for great political uncertainty in the event of no satisfactory (or any) deal being reached, feel – at least to UK residents – more prominent in our lives at this moment than some of these wider issues.

The Brexit affair

Whichever way one voted, it is hard not to be dismayed by the shambles that is Brexit, concocted by all sides. Until recently, the UK appeared to have no clearly defined strategy. Its negotiations are led by a PM who wanted to remain, receiving criticism from the right wing of her party for not going far enough, and daily criticism from the opposition party, led by a long-time Eurosceptic, that still has no credible alternative aside from six ‘cake-and-eat-it’ criteria that any deal must meet. For example, Criteria 2 poses the question ‘Does it deliver the “exact same benefits” as we currently have as members of the Single Market and Customs Union?[2]’, which is an impossibility, unless the deal is to remain. What a mess! One would laugh if the consequences for our nation were not so great.

The EU has hardly covered itself in glory either with their intransigence and deep-seated, implicit desire to make everything so tough that other EU member states won’t dare to follow suit, or that UK voters might change their minds. Yanis Varoufakis – the Greek finance minister at the time of their debt crisis – revealed the trap that the EU would set for the UK government, in his book[3] about his own experiences of dealing with it. Did any of our politicians read it?

In the event that any deal agreed gets voted down in Parliament – or there is no deal – we face a high chance that the Conservative government could fall (but will turkeys vote for Christmas?) to be replaced by a far-left leaning government led by Corbyn and McDonnell. Whatever your own thoughts and preferences on that, the one certainty is that we would be in for a period of radical change. Certainly that means higher personal taxation. In Labour’s 2017 manifesto they gave us a clue: a 45% income tax rate to kick in at £80,000 of income, with a 50% rate above £123,000. This results in marginal tax rates – taking into account National Insurance and tapering of allowances – of 55% for those earning between £80,000 to £100,000, 73% up to £123,000 and 58% thereafter, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Even before these changes it is interesting to note that 4 in 10 adults currently pay no income tax and the top 10% of income tax payers pay 60% of all income tax[4] and around 30% of all personal taxes collected. Corporation tax is set to rise from 19% to 26% and the 10% shareholding held for employees – announced by McDonnell at the Labour Party Conference – is likely to be a large new tax on companies, given the £500 limit per employee on dividend income and with the remainder going to HMRC. Renationalisation of some industries, possibly without full compensation, is not beyond the realms of possibility. Wherever you sit in terms of the balance between equity (how the economic pie is sliced up) and efficiency (how big the pie is), there is no doubt that we are living in ‘interesting’ times.

The point of this note is to recognise that the world we live in can be an uncertain and uncomfortable place and it can create anxiety over our future wealth and well-being. It also sets the context for why and how a sensibly structured portfolio can provide considerable comfort for longer-term investors, and how we can put the uncomfortable noise of what’s going on in perspective.

It is not all bad, in fact, far from it

A recent study by the OECD[5] projects that global (after inflation) growth will rise by 3.7% in both 2018 and 2019, with major European economies growing by 1% to 2%, including the UK (1.3%). Growth in the US is predicted to be around 3% in 2018 and 2019. In the UK, employment is at a record high and real wage growth (after inflation) has been positive since 2015 and the budget deficit is now around 1% of GDP compared to 10% before the austerity program. Global growth leads to a growth in global earnings, which, when added to dividends paid, equates to the economic return due to equity investors for providing capital. That’s good news.

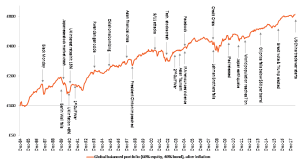

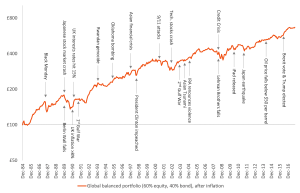

The chart below illustrates that markets weather the multitude of World events they experience, rewarding the patient long-term investor, with growth in their purchasing power.

Figure 1: The relentless growth of purchasing power, despite World events (1/1985-7/2018)

Source: Albion Strategic Consulting[6]

The capitalist spirit continues to drive positive change

Since 2016 alone, 90 million people have been lifted out of extreme poverty[7], something that afflicts 8% (634 million) of the World’s population, most of whom live in Sub-Saharan Africa. South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific have lifted around 0.5 bn and 1 bn people out of extreme poverty, respectively, since 1990[8]. That is on account of the unleashing of the energy and innovation that capitalism has driven in these regions, including China. In terms of infant mortality, the progress has, again, been staggering. In 1990, on a global basis, infant mortality stood at 65 deaths per 1,000 live births. Today it is less than half that at below 30[9]. This is due to the reduction in poverty and improvement in healthcare and education around the globe, again driven and funded by the wealth that capitalism delivers[10].

Please take the time to view an amazing data visualisation of the World’s progress since 1810 by Hans Rosling[11], a renowned global health academic, to lift your spirits (see footnote 8). It’s a great way to spend four minutes.

We, as humans, tend to hold many misperceptions around important issues, overestimating guesses when an issue worries us and underestimating those that do not. In part, this is because we rely on the fast thinking part of our brains, which are often not over-ridden by slower, more measured, reasoning[12]. For example in the UK we guess that 37% of the population is over 65, when in fact it is 17%. We believe that the top 1% of wealthiest people own 59% of the wealth, when in fact it is 23%. Only 13% of the UK’s population are immigrants, yet we guess at 25%[13]. One can begin to see how polarised political system can use facts and misperceptions to their advantage.

So where does all this leave investors and their portfolios?

You may well be asking yourself whether what is going on in the World affects how your money is invested and if any changes need to be made to your portfolio. The question implicitly suggests that we can look into the future and know what is going to happen. If it were that easy, all investors would know what to do and prices would already have moved. Remember that you are not the only person thinking about these global challenges and all scenarios are reflected in current prices. As a consequence, we need to rely on the structure of our portfolios to see us through.

We set out three key risks relating to Brexit and how sensible portfolio structures can mitigate them.

Risk 1: Greater volatility in the UK and possibly other equity markets

In the event of a poorly received deal – or no deal – it is certainly possible that the UK equity market could suffer a market fall as it tries to come to terms with what this means for the UK economy and the impact on the wider global economy. A collapse of the Conservative government and a Labour victory would add further uncertainty.

Risk 2: A fall in Sterling against other currencies

In 2016, after the referendum, Sterling fell against the major currencies including the US dollar and the Euro. There is certainly a risk that Sterling could fall further in the event of a poor/no deal.

Risk 3: A rise in UK bond yields (and thus a fall in bond prices)

The economic impact of a poor/no deal and/or a high spending socialist government could put pressure on the cost of borrowing, with investors in bonds issued by the UK Government (and UK corporations) demanding higher yields on these bonds in compensation for the greater perceived risks. Bond yield rises mean bond price falls, which will take time to recoup through the higher yields on offer.

Looked at in isolation, these may appear to be significant risks. Owning a well-diversified and sensibly constructed portfolio, however, can greatly reduce these risks.

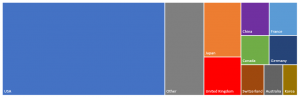

Mitigant 1: Global diversification of equity exposure

Although it is the World’s sixth largest economy (depending on how you measure it), the UK produces 3% to 4% of global GDP, and its equity market is around 6% of global market capitalisation. Many of the companies listed on the London Stock Exchange derive much of their revenue from outside of the UK (around 70% to 80%). For example, HSBC, even though it is often thought of as a British bank, generates over 90% of its revenues from overseas. Well-structured portfolios hold diversified exposure to many markets and companies.

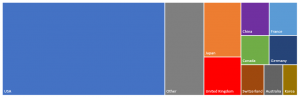

Figure 2: Global market capitalisation (developed and emerging markets) – 2018

Source: Albion Strategic Consulting using data from iShares – August 2018 (MSCI ACWI ETF).

Equity markets are always volatile, responding – sometimes materially – to new information. Despite this, changing your mix between bonds and equities would be ill-advised. Timing when to get in and out of markets is notoriously difficult. Markets move with speed and magnitude and missing out on the best days in the markets can have material long-term return impacts. Provided you do not need the money today, you should hold your nerve and stick with your strategy.

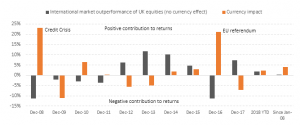

Mitigant 2: Owning non-Sterling assets and currencies in the growth assets

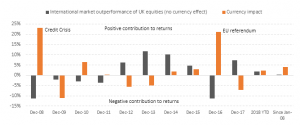

In the event that Sterling is hit hard, it is worth remembering that the overseas equities that you own come with the currency exposure linked to those assets. For example, owning US equities comes with US dollar exposure, as this exposure is not hedged out. In short, a fall in Sterling has a positive effect on non-UK assets that are unhedged. The chart below illustrates the impact that currency in unhedged non-UK assets has had over the past decade. As you can see, at times of market crisis, the Pound has fallen against other safe-haven currencies such as the US dollar.

Figure 3: A falling pound is a positive contributor to portfolio returns

Source: Morningstar Direct© 2018. All rights reserved. Data derived from MSCI World Index in GBP, MSCI World Index in Local Currency and MSCI UK Index.

The bond element of your portfolio should have little or no non-Sterling currency exposure to avoid mixing the higher volatility of currency movements with the lower volatility of shorter-dated bonds.

Mitigant 3: Owning short-dated, high quality and globally diversified bonds

Any bonds you own should be predominantly high quality to act as a strong defensive position against falls in equity markets. Avoiding over-exposure to lower quality (e.g. high yield, sub-investment grade) bonds makes sense as they tend to act more like equities at times of economic and equity market crisis. Your bond holdings should be diversified across a number of different global bond markets, which mitigates the risk of a rise in UK yields (and thus falling prices), as the cost of borrowing in other markets may not be impacted in the same way, at the same time.

Some thoughts to leave you with

Even if you cannot avoid watching, hearing or reading the news, it is important to keep things in perspective. The UK is a strong economy with a strong democracy. It will survive Brexit, whatever the short-term consequences that we will have to bear, and so will your portfolio. Keeping faith with both global capitalism and the structure of your portfolio and holding your nerve, accompanied by periodic rebalancing is key. Lean on your adviser if you need support. That is what we are here for.

Perhaps try to catch up on the news only once a week and use the extra time to read about some of the exciting and positive things that are happening in the World.

‘This too shall pass’ as the investment legend Jack Bogle likes to say.

Other notes and risk warnings

Use of Morningstar Direct© data

© Morningstar 2018. All rights reserved. The information contained herein: (1) is proprietary to Morningstar and/or its content providers; (2) may not be copied, adapted or distributed; and (3) is not warranted to be accurate, complete or timely. Neither Morningstar nor its content providers are responsible for any damages or losses arising from any use of this information, except where such damages or losses cannot be limited or excluded by law in your jurisdiction. Past financial performance is no guarantee of future results.

Risk warnings

This article is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered investment advice or an offer of any security for sale. This article contains the opinions of the author but not necessarily the Firm and does not represent a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed.

Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that the stated results will be replicated.

Other notes and risk warnings

This article is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered investment advice or an offer of any product for sale. This article contains the opinions of the author but not necessarily the Firm and does not represent a recommendation of any security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed.

Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that the stated results will be replicated.

[1] The Economist, September 22nd – 28th edition, ‘Hunker down’, page 12.

[2] www.labourlist.org (2017) Keir Starmer: Labour has six tests for Brexit – if they’re not met we won’t back the final deal in parliament. 27th March 2016.

[3] Yannis Varoufakis (2016), And the weak suffer what they must The Weak Suffer What They Must? Europe’s Crisis and America’s Economic Future, New York: Nation Books, 2016

[4] IFS (2017) www.ifs.org.uk/publications/10038 Note also that an income of a little over £50,000 put one in the top 10%.

[5] OECD Economic Outlook and Interim Economic Outlook (September 2018) http://www.oecd.org/eco/outlook/economic-outlook/

[6] Global balanced portfolio: 36% MSCI World Index (net div.), 26% Dimensional Global Targeted Value Index, 40% Citi World Government Bond Index 1-5 Years (hedged to GBP) – no costs deducted, for illustrative purposes only. Data source: Morningstar Direct © All rights reserved, Dimensional Fund Advisers. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

[7] World Poverty Clock www.worldpoverty.io (worth a look at how poverty is reducing).

[8] The Economist, September 22nd – 28th edition, ‘Poverty estimates’, page 65.

[9] World Bank (2017) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN?end=2017&start=1990

[10] For any reader interested in a more positive outlook, Matt Ridley’s book ‘The Rational Optimist’ is a good read

[11] Hans Rosling’s data visualisation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jbkSRLYSojo – a brilliant four minutes!

[12] Nobel Prize winner, Daniel Kahneman’s book ‘Thinking fast and slow’ is a great read on this subject.

[13] Data source: Bobby Duffy (2018), ‘The Perils of Perception: why we are wrong about nearly everything’. Bell & Bain Ltd. Glasgow. A great read on the subject.

Recent Comments